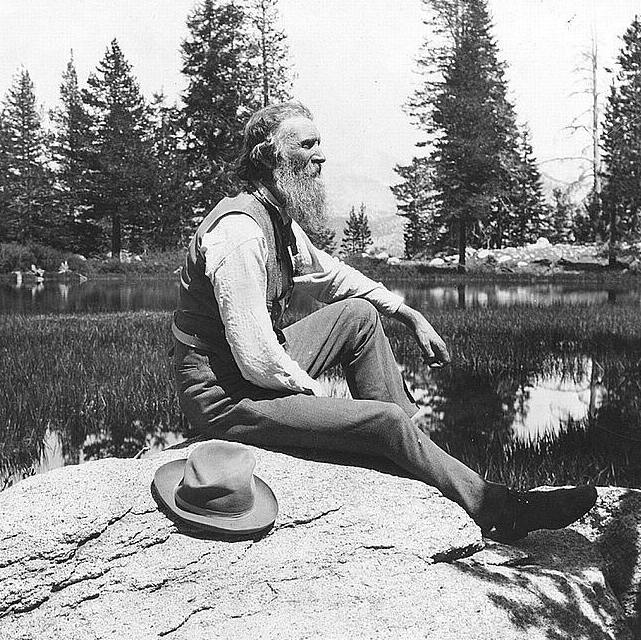

Ironically, it was while recovering from an accident that had left him blind for several months that John Muir, the “father of the U.S. parks system,” decided to devote his life to conservation.

Videos by TravelAwaits

Today, more than 200 million visitors annually enjoy the 84 million acres of national parks that sprung from Muir’s epiphany. From the calving glaciers in Alaska’s Glacier Bay to the manatees of Florida’s Everglades, there’s much to explore! Here are nine surprising facts about the man whose vision — or lack thereof — left this legacy:

1. John Muir Was Not Born In America

Like many of us, I had assumed that this iconic figurehead of American conservation was born in the U.S. But Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, a sunny village about an hour south of Edinburgh.

His family lived above his father’s meal (oat) shop. Oats were an important staple for many Scots, for both animal feed as well as ubiquitous Scottish porridge, so the family was quite prosperous.

John attributed his love of nature to tramping in the Scottish countryside. In The Story of My Boyhood and Youth, he wrote:

“When I was a boy in Scotland, I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life I’ve been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures.”

“When I was a boy in Scotland, I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life I’ve been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures.”

Pro Tip: The three-story home where John grew up in Dunbar is now a museum cataloging John’s many achievements. My favorite exhibit was the two first editions of Muir’s books, published in 1894 and 1913.

2. Muir Taught Himself About Botany And Biology

John’s father, Daniel, was an evangelical Christian and a harsh disciplinarian. John later wrote:

“Father made me learn so many Bible verses every day that by the time I was 11 years of age I had about three-fourths of the Old Testament and all of the New by heart and by sore flesh.”

As the elder Muir’s religious beliefs became more extreme, he decided to leave Scotland to join the strict American-based Disciples of Christ. Packing up 11-year-old John, his older sister, and younger brother, Daniel set sail for the New World, eventually settling on uncultivated land in Wisconsin to establish a home and farm before bringing over his wife and four other children.

Daniel wouldn’t allow John to go to school, as he was needed to break the tough land from sunup to sundown. But John borrowed books and taught himself botany, biology, and geology. He’d rise at 1 a.m. to study in the basement until sunrise.

John also learned by roaming the fields, cataloging plants, and documenting trees. He loved this land so much that, as an adult, he tried three times to purchase his boyhood farm. Today, Fountain Lake Farm is a National Historic Landmark open to visitors.

3. Muir Invented A Contraption To Propel Him Out Of Bed

With no technical training, John invented things – mostly clocks and barometers and a machine to automatically feed horses – but also a contraption to flip him out of bed every morning! He took his “early rising machine” to the Madison State Fair, where he attracted attention from the University of Wisconsin, which awarded him a scholarship – even though he was self-taught and had no high school diploma.

Once enrolled at Madison, he invented a “study desk” to open books and turn the pages. Sunlight would burn a thread that was connected to a lens, ensuring that the contraption would be set off at sunrise. The desk is on display at the Wisconsin Historical Society on UofW/Madison’s campus.

During a stint as a teacher, he invented a clock that could light the classroom’s fire early each morning so the room was warmed by the time the students arrived.

He took a hodge-podge of classes for four years before dropping out, preferring his outdoor botanical studies. He wrote:

“I was only leaving one University for another, the Wisconsin University for the University of the Wilderness.”

4. Muir Lost His Eyesight

To earn a living, Muir put his knowledge of mechanics to good use by working at factories – and usually invented ways to improve production. He ended up in Indianapolis, which was then a post-Civil War industrial hub, but still near forests and swamps so he could continue his “University of the Wilderness” education.

At 28, Muir started working at a carriage factory. Impressed with their new employee’s skills, the owners offered him a partnership. But while tightening a spinning belt, Muir lost his grip and the metal awl slipped and cut the cornea of his right eye, blinding him. Although his left eye was uninjured, it fell into “sympathetic” blindness, and Muir was “closed forever on all God’s beauty,” as he cried out after the accident.

He was confined to bed in a dark room for two weeks and slipped into a deep depression. He wrote home, “I have been groping among the flowers a good deal lately.”

When the bandages were removed six weeks later, Muir’s sight was restored. But this frightening accident had given him a new vision:

“I bade adieu to all my mechanical inventions, determined to devote the rest of my life to the study of the inventions of God.”

5. Muir Was An Early Guide In Yosemite

After walking from Louisville, Kentucky, to Florida by “the wildest route possible” (a journey chronicled in his book A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf) and a side trip to Havana, Cuba, Muir headed for California. He had read an account about Yosemite and that’s where he set his new sights.

By the time Muir first visited Yosemite, it had become a stomping ground for rugged San Franciscans. After descending into the valley via 26 arduous switchbacks, they would stay in one of a few rustic inns – or “camp out in the forests, eating oatcakes and drinking tea, hiking to mountain vistas such as Glacier Point, reading poetry around campfires and yodeling across moonlit lakes,” writes Tony Perrottet in Smithsonian Magazine.

Muir first arrived in 1868 and stayed for about 10 days. He returned the following year and landed a job building and running a sawmill for one of the innkeepers. He guided tourists, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, who visited specifically to meet the young naturalist.

Muir spent most of the next six years in Yosemite filling notebook after notebook with his observations of plants and geological formations. He earned a reputation in San Francisco as a self-taught naturalist and began writing articles for leading magazines of the time — Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and the New York Tribune, eventually concluding he needed to spend more time protecting Yosemite than delighting in it.

6. Muir Toured Teddy Roosevelt Through Yosemite

The President personally wrote to Muir in 1901, requesting a tour through Yosemite. “I do not want anyone with me but you,” Roosevelt wrote, “and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

In the spring of 1903, Muir traveled for two months with Roosevelt from the White House to Yellowstone with dozens of flesh-pressing stops along the way. He detailed his two-week camping tour of Yellowstone in an incredible 1906 Atlantic Monthly article.

Later that year, Muir toured the President on a 4-day trip through Yosemite. Roosevelt ditched his security detail and set out with Muir on a trip of “rough sleeping,” as Muir’s Scots would say. One morning, they awoke dusted in snow, to which Roosevelt responded, “This is bullier yet.”

However, Muir didn’t “drop” the politics. He wanted Roosevelt to declare Yosemite a national park – as Yellowstone had recently been by President Ulysses S. Grant. Of the trip, Muir later wrote, “I stuffed him pretty well regarding the timber thieves, and the destructive work of lumbermen and other spoilers of the forest.”

During his presidency, Roosevelt would preserve more than 230 million acres of public land, including Yosemite and four other national parks and 18 national monuments.

7. Muir Cofounded The Sierra Club

In 1892, to protect his beloved Yosemite and “to make the mountains glad,” Muir co-founded the Sierra Club, America’s oldest and most enduring environmental organization, and was its president until his death in 1914.

Today, Sierra Club, along with the rest of America, is examining its institutional racism, apologizing for its founder’s racist attitudes.

“[Muir] made derogatory comments about Black people and Indigenous peoples that drew on deeply harmful racist stereotypes, though his views evolved later in his life,” Michael Brune, the Club’s executive director, wrote on the group’s website. “As the most iconic figure in Sierra Club history, Muir’s words and actions carry an especially heavy weight. They continue to hurt and alienate Indigenous people and people of color.

“For all the harms the Sierra Club has caused, and continues to cause, to Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color, I am deeply sorry.”

8. Muir Woods Is Named After Him

Roosevelt named Muir Woods – the towering redwood forest north of San Francisco – as a national monument in honor of his friend. And there’s the John Muir College, part of the University of California/San Diego, which promotes environmental studies.

But it’s the John Muir Trail, one of America’s premier hiking trails, that really exemplifies Muir’s legacy. The 210-mile trail starts, of course, at Yosemite National Park, stretches through Ansel Adams Wilderness, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, and ends at continental America’s highest peak, Mt. Whitney.

9. Muir Navigated The Globe

To spark people’s interest in nature, Muir wrote 12 books and more than 300 articles about nature and his travels – which took him to every continent (except Antarctica). In 1903, he set out on a world tour through Europe, Siberia, the Far East, India, Egypt, Australia.

But, for Muir, “the clearest way into the universe [was] through a forest wilderness.”

Related Reading: